Sheikh Abdullah And The Fall Of Feudal Kashmir

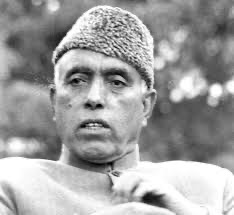

In the sun-dappled valley of Kashmir, where mountains rise like ancient sentinels and rivers whisper stories into the earth, a quiet revolution once surged. At the heart of this transformation stood Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah—reverently known as the “Lion of Kashmir”—a towering figure whose political imagination and legislative foresight redefined the social contract of the region.

He was not the inheritor of an empire nor the son of a dynasty. Born in 1905 in the modest town of Soura, Sheikh Abdullah’s rise was not foretold—it was forged. His journey from Islamia School in Srinagar to a master’s degree in Chemistry from Aligarh Muslim University mirrored the awakening of a people long denied their voice. But his chemistry was not confined to molecules; it was the alchemy of society, a vision to transmute bondage into dignity.

“Khudi ko kar buland itna ke har taqdeer se pehle

Khuda bande se khud pooche, bata teri raza kya hai.” —Allama Iqbal

Kashmir, though abundant in natural beauty, was for centuries shackled by a feudal order where land was privilege, not home; inheritance, not right. The peasantry, whose hands nurtured the earth, had no claim to it. Systems like jagirdari and chakdari were soft names for hard chains. It was in this context that Sheikh Abdullah’s leadership struck at the roots of inequality. In 1950, the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act—widely known as the “Land to the Tiller” law—was enacted under his leadership.

It was not merely a statute; it was a sermon of justice. The law capped land ownership at 22 standard acres, and surplus land was transferred to those who actually tilled it.

Over 192,652 acres of land were distributed among 160,939 tillers—men and women whose shadows once bent before landlords now stood upright in the light of self-determination.

This was no violent upheaval, no bolshevik storm—it was a silent earthquake that shook a thousand-year-old structure to its core. With one stroke of the pen, Sheikh Abdullah turned peasants into proprietors and furrows of despair into rows of hope.

“Sultani-e-jamhoor ka aata hai zamana,

Jo naqsh-e-kuhan tum ko nazar aaye mita do.” —Allama Iqbal

The law was revolutionary not only in its economic scope but also in its spiritual depth.

It uprooted the metaphors of master and servant, elite and expendable, estate and estate-less. Sheikh Abdullah did not just transfer ownership; he transformed identity.

He altered the very relationship between a person and their soil, turning cultivation into citizenship and toil into triumph. The ‘Land to the Tiller’ Act realized the Naya Kashmir Manifesto of 1944—a visionary document that promised universal education, gender justice, economic equity, and the end of exploitative structures. For once, a manifesto was not a tool to capture power but a blueprint to redistribute it.

Sheikh Abdullah’s reforms went further. The State Tenancy Act of 1924 was amended to safeguard tenants’ rights. The J&K Agrarian Reforms Act of 1976 reinforced the egalitarian spirit by limiting landholdings further and empowering tillers.

These legal interventions symbolized a deep restructuring of social hierarchies, breaking the spine of feudal privilege and restoring the dignity of labor. Although, like many bold reforms, implementation faced hurdles. The bureaucracy—often still tied to elite interests—betrayed the spirit of the law. Landowners manipulated loopholes, retaining the choicest land while relinquishing less desirable parcels.

This partial sabotage diluted the impact and allowed fragments of inequality to persist.

Yet, despite its imperfections, the law remains a monument to visionary leadership.

“Gharibon ka jo haq hai woh unko milay,

Kaheen se na ho zillat-e-admi.” —Allama Iqbal

Let it not be said that Kashmir has not known visionaries. Sheikh Abdullah’s nationalism was secular and inclusive.

He envisioned not partition, nor mere accession, but dignity—rooted in fraternity and freedom—for every Kashmiri soul. His politics was not built on sect or caste but on the broken backs of laborers now walking tall.

His legacy is not carved into statues, but into lives. In the homes built on once-feudal lands, in schools standing where peasants once bowed, in the songs sung by the children of former sharecroppers—his revolution echoes still.

Sheikh Abdullah dared not only to dream, but to legislate justice and root it in reality.

In this age, when governance is too often equated with dominion and populism with principle, we must return to this chapter not out of nostalgia, but reverence.

Sheikh Abdullah’s reforms challenge us to ask: can there be peace without justice, stability without equity, or governance without dignity?

He sowed a revolution with ploughshares, not swords. His dream was written in soil, watered by justice, and harvested by history.

“Main ne mitti ko watan banaya.”

—I made the earth into a homeland.

In the quiet fields of Kashmir, where once the tiller bowed to the landlord, now stands the echo of a leader who dared to dream. He did not merely redistribute land; he sowed dignity. He did not merely pass laws; he ploughed justice into the earth.

As Kashmir grapples with new political realities, it must ask whether a future built without equity can ever stand.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s land reforms are not just relics of the past; they are living testaments to what governance rooted in moral clarity can achieve.

“Zara nam ho to yeh mitti bohat zarkhez hai, saqi.” —Allama Iqbal

If watered with hope and justice, this land can bloom again.

Author

Name: Yasir Ganderbali

Student of law, at Central University of Kashmir, Ganderbal